Vicennial

13 July – 19 August 2017

Alison Unsworth, Waiting, 2017, inkjet print on Hahnemühle paper, 30x30cm, edition of 3

Dodda Maggý, Étude Op. 11, 2017, video, 5:30min

Barbara Walker, Tableau III, 2016, graphite and paper on digital print, 70x54cm

EC Davies, Snakes and Ladders, 2017, video, 3:14min

EC Davies, Michael Davies, Kerstin Drechsel, Jorn Ebner, Mark Joshua Epstein, Nick Fox, Simon Le Ruez, Dodda Maggý, Jock Mooney, Michael Mulvihill, Stephen Palmer, Josué Pellot, Narbi Price, Morten Schelde, Matthew Smith, Alison Unsworth, Barbara Walker, Miranda Whall, Flora Whiteley

‘Vicennial’ celebrates twenty years of Vane. In July 1997 Vane opened our first ever exhibition. In the twenty years since then we have worked with hundreds of artists from around the world, both welcoming them to our home in the north east of England as well as through taking the gallery to participate in international projects in Denmark, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the USA.

‘Vicennial’ consists of work from nineteen artists who have shown at the gallery during our history. The artists come from across the UK, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Puerto Rico, South Africa, and the USA.

In EC Davies’ video animation, Snakes and Ladders (2017), three masked characters methodically walk up a set of invisible stairs and subsequently roll down the screen from the other side, all against an abstracted landscape of glittery fabric. The soundtrack for the piece is made from recordings of voices and is quiet and hypnotic, reflecting on the ritual and magic of the everyday.

Michael Davies’ painting, She’s leaving (and I feel like dying) (2017), shows an almost monochrome image of grotesquely twisted trees, leafless, blackened and brutally lopped. The painting is a spatial study or ‘serving suggestion’ from a half-finished, over-complicated and semi-abandoned painting, SEEYOUNEXTTUESDA... (2016), an apparently failed attempt at a response by the artist to Brexit.

Kerstin Drechsel’s risograph print from the series ‘Pflegekind 2’ (nursing-child 2) (2017) combines two unconnected motifs in a wallpaper-like pattern: one an allusion to political resistance in which a woman holds two breast-like megaphones. The other motif shows a plant found by the artist on a street in Berlin, with a sign ‘Plegekind 2 - nursing-child 2, please don't steal it. Thank you!’, an allusion to motherhood, to caring or nurturing.

Jorn Ebner’s drawing, 1562 (Pieter Bruegel) (2017), is taken from a Pieter Bruegel the Elder drawing of three blind men, deconstructing the figures into a network of lines, three denser areas corresponding to the figures and fainter lines a hazy background. Bruegel’s original refers to the Biblical parable of the blind leading the blind, a reflection on political upheaval in The Netherlands of the 16th century that has resonance today.

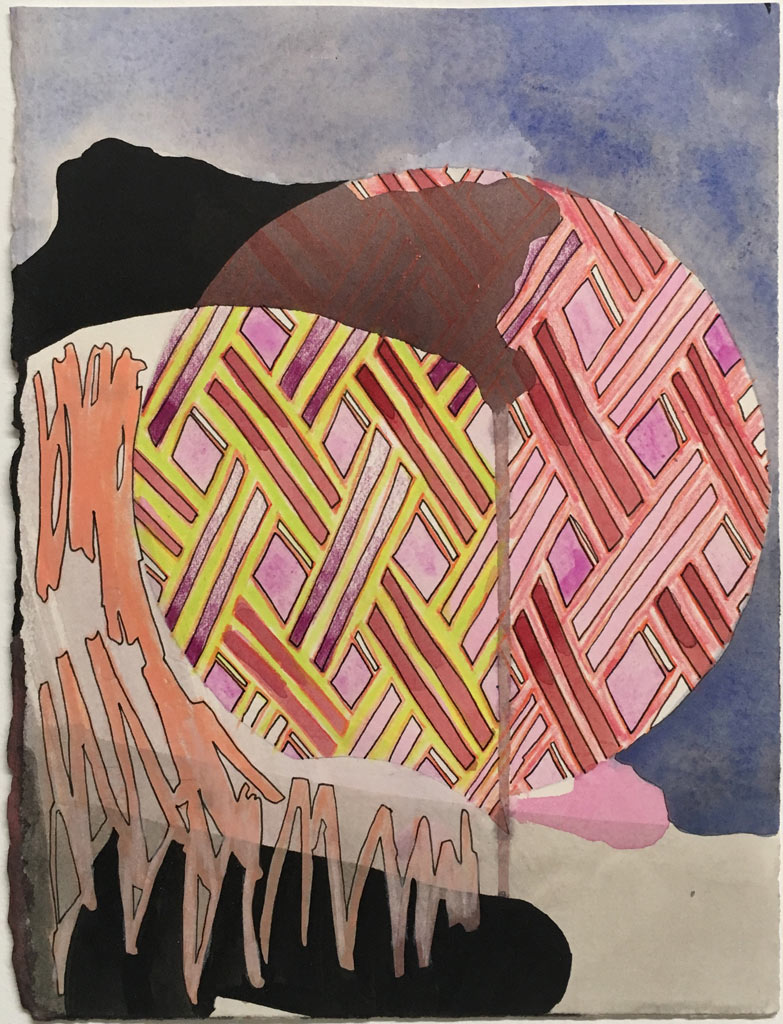

In his painting, Untitled (pattern circle) (2016), Mark Joshua Epstein both reveals and obscures an apparently clumsily rendered circle of pattern, reminiscent of a 1920s Art Deco textile or stained glass window. This pattern is cut up and obfuscated by successive layers of poured paint and harshly rendered, jagged pattern, creating an image at once both exuberant and brooding, brash and baroque.

In Nick Fox’s drawing, This longing (figure 3) (2006), the image of a naked young man is transformed into one of intimacy and emotive experience. The figure stands as if posed for the artist, whist overlaid botanical imagery fuses a symbolic role to his themes of desire, longing and loss. This tantalising idyll and elusive narrative is rendered in dark ochre, creating a toxic miasma, an Eden after the fall where innocence has been banished.

In Simon Le Ruez’s drawing, Ludwig’s dream #2 (2016), a depiction of a grey and monumental castle sheds its inhibitions and gives way to a spirited and flamboyant release of colour, evoking meeting points, and exuding a playful sense of the inside coming out. The title refers to the 19th century King of Bavaria, Ludwig II, who spent his reign as a recluse, indulging in extravagant architectural projects such as his fairytale castles.

In Dodda Maggý’s video animation, Étude Op. 11 (2017), a stationary ‘opal’ starts to loop erratically around a black background, gradually more opals appear until there are eleven of different sizes and subtle colours apparently describing the lines of an invisible image. As the opals move across the dark surface, the eye adds information to the missing image. One by one they vanish returning to the single dot. Vision meets the mind’s eye.

In his screenprint, Brexit Cat (2017), Jock Mooney presents an image inspired in part by folk art, part classical mythology and part manga comics. A cartoon-like black cat is shown expelling from both ends, but these expulsions are magically transformed into pink and white flowers as if spilling from a cornucopia. The title suggests the artist is making a wry comment on the uncertainty of the country’s political future.

Michael Mulvihill’s drawing, LOW-002 (45 minutes: the jubilant villagers) (2001-15), started with drawings made from newspaper front pages shortly after the invasion of Afghanistan following the attack on the World Trade Centre in 2001, and only assembled fourteen years later as a single art work, creating a palimpsest of the artist’s response to apocalyptic events asking how is art made the day after the end of history?

In his drawing, Nothing to do (2017), Stephen Palmer uses a process both random and controlled. A piece of scrunched-up paper has been unfolded as if to mend this flawed and damaged item. The subject for a highly detailed drawing, rendered in pencil on another sheet of paper, the austere beauty of the resulting work reflects both an undoing of formal abstraction’s geometry and – in uncertain times – a celebration of negation as a positive, creative act.

Josué Pellot’s two-piece painting, Double Bluff (2016), is taken from an airline safety information sheet from the 1970s. In both panels the identical graphic image of a jet liner is shown performing an emergency ‘landing’: one into water, the other onto land. The title refers to the implicit fiction that either scenario is survivable, when we know the possibility is remote. Pellot shows us the power of perception, iconography and collective belief.

In Untitled Lamp Painting (Room 253) (2017), Narbi Price shows the dark and brooding image of an old-fashioned wall lamp faintly illuminating an hotel room number and the shadowy edge of a door. Behind the image is the story of crime writer Agatha Christie’s dramatic disappearance in December 1926. After an eleven-day nationwide manhunt, she was found in a confused state in Room 253 of an hotel in Harrogate.

In Morten Schelde’s drawing, Interior (2017), we are drawn into a disturbing world of psychological exploration and primal fears, where the physical meets imaginary space, reality and fiction intermingle, and the unfamiliar penetrates. We stand in a conventional, homely living room that has been invaded by floating, leprous, yellow excrescences, whilst, most disturbingly of all, a vague, shadowy figure stands at the top of the staircase.

In the collage, Untitled (Every rock from National Geographic magazine November 2014) (2015), Matthew Smith cuts out every rock from photographs in an issue of National Geographic magazine and stacks them in a single pile. By creating a ‘fake’ landscape from elements of the real, Smith does not present an image of sublime nature; rather, he produces a sense of the uncertainty and unpredictability of the human world.

In her print, Waiting (2017), Alison Unsworth blurs the boundaries between the natural and the urban environment. A pattern is created from a varied arrangement of hooded crows, mountains and telegraph poles, graphic and highly stylized. It was originally designed as a wallpaper for a waiting area at the Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow, where viewers could spend time spotting differences and similarities.

Barbara Walker’s collage, Tableaux III (2016), is part of an examination of the contribution of black servicemen and women to the British Armed Forces since 1914. Walker reflects on contemporary British conflicts alongside historical ones involving Britain and the colonised nations of the British Empire and the contributions of the British West Indies Regiment and the King’s African Rifles, among others. This includes addressing gender and the under-recognised role of servicewomen from the Caribbean and West India Regiments in World War II.

In her video, Llwybrau’r Defaid (1) (2017), Miranda Whall appears as a kind of cyborg sheep/human. Wearing a sheep fleece, she crawls for five and a half miles along sheep tracks in the bio-diverse upland area of the Cambrian Mountains in west Wales to the accompaniment of a flute. In a humorous way, Whall attempts to experience and understand the mountain intuitively with her body, altered and in motion.

Flora Whiteley’s Untitled (2017) drawing shows an unoccupied Hollywood apartment from the early 20th century taken from a contemporary photograph. Shrouded items of furniture appear as ghostly presences: echoes of the former inhabitants. The drawing is part of a series of interiors acting as vessels; housing memories, histories and feelings. These spaces are to be explored emotionally rather than simply being an architectural construct.

‘Vicennial’, 2017, installation view.

Take a video tour of the exhibition

Share this page